Adam Walsh Act

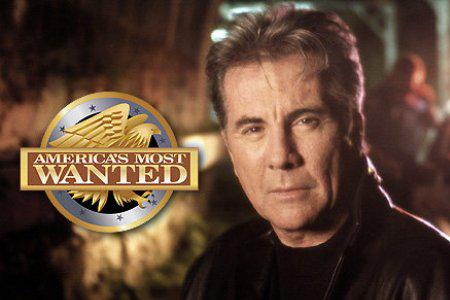

“…and remember, you can make a difference.”

-America’s Most Wanted (1988-2012), John Walsh

Walsh is known for his anti-crime activism and his extreme hatred of criminals, with which he became involved following the murder of his son, Adam, in 1981.

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act is a federal statute that was signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on July 27, 2006. The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act (AWA) was signed on the 25th anniversary of the abduction of Adam Walsh from a shopping mall in Florida. Adam Walsh was found murdered 16 days after his abduction in 1981.

When USCIS receives an AWA Case, it will consider the following questions:

- Whether the classification of a particular conviction as a “specified offense against a minor” was to be done using a “categorical” analysis, in which only the elements of the state crime were analyzed, rather than the actual conduct of the United States citizen petitioner;

- Whether the USCIS was correct in interpreting the “no risk” element of the AWA to mean that petitioners must provide evidence showing “beyond a reasonable doubt” (which is the standard used in criminal proceedings) that they weren’t a threat to their own relatives, or whether the ordinary “preponderance of the evidence” standard should be used;

- Whether it was the government’s job to prove the existence of a disqualifying petition, or if that job fell to the petitioner;

- Whether a petitioner could appeal certain legal aspects of a “no-risk” determination, or whether the BIA lacked jurisdiction even over these non-discretionary issues; and

- Whether the AWA would apply to an individual whose disqualifying offense happened before the new law took effect.

What is the Goal of the Adam Walsh Act?

The goal of the Adam Walsh Act is to protect children from sexual exploitation and violent crimes, to prevent child abuse and child pornography, to promote Internet safety and to honor the memory of Adam Walsh and other child crime victims.

What Does the Adam Walsh Act Do?

The Adam Walsh Act categorizes sex offenders into three tiers according to the crime committed, and mandates the following:

- Tier 3 offenders (the most serious tier) update their whereabouts every three months with lifetime registration requirements;

- Tier 2 offenders must update their whereabouts every six months with 25 years of registration; and

- Tier 1 offenders must update their whereabouts every year with 15 years of registration. Failure to register and update information is a felony under the law. States are required to publicly disclose information of Tier 2 and Tier 3 offenders, at minimum.

The Act also creates a national sex offender registry and instructs each state and territory to apply identical criteria for posting offender data on the internet (i.e., offender’s name, address, date of birth, place of employment, photograph, etc.). It also contains civil commitment provisions for sexually dangerous people.

How Does AWA Affect Family-Based Immigrant Visa Process?

The AWA has, for the first time, limited the rights of U.S. citizens (USCs) or lawful permanent residents (LPRs) to sponsor their relative (including fiancés) to immigrate to the U.S. if the petitioner has a listed child sex abuse conviction. If this is the case, then the petition cannot be approved unless the Department of Homeland Security determines in its unreviewable discretion that there is no risk of harm to the beneficiary or derivative beneficiary.

Which Petitions Fall Under the AWA?

The AWA applies to Form I-130, Petition for Alien Relative as well as Form I-129F, Petition for Alien Fiancé. In every family-based sponsorship, a “petitioner” (either a lawful permanent resident or U.S. citizen) must file Form I-130 or I-129F for a “beneficiary.”

Can USCIS Find Out This Is an AWA Case?

Absolutely. For immediate relatives, the relative petition and adjustment of status application (along with the employment authorization and advance parole applications) can be filed all together. For family-based preferences, the relative petition must be approved and the file sent to the National Visa Center (NVC) which will assess the availability of an immigrant visa. If an immigrant visa is available, the NVC will notify the beneficiary that he or she may submit an immigrant petition online. In both circumstances, once an immigrant petition is submitted, the beneficiary then becomes the green card “applicant.”

When filing the petition, the petitioner must provide identifying information, including name, birth date, social security number, and proof of citizenship. USCIS may use this information to search for a criminal history. If USCIS discovers that the petitioner has any conviction that might possibly be for a “specified offense against a minor,” the burden shifts to the petitioner to prove that he or she was not convicted of such an offense (for example, that the offense was not “against a minor” because the victim was over 18 years old).

What Makes an AWA Case Different From All Other Family-Based Sponsorship Cases?

There are four main differences. First, the processing time for AWA cases is almost always longer. Second, in non-AWA cases, a biometrics appointment is only issued to the applicant to make sure he or she is “admissible.” In AWA cases, the beneficiary and the petitioner will have their biometrics taken. Third, the petitioner will be required to prove that he or she poses no threat to the beneficiary. At a minimum, the petitioner will need to submit copies of police reports, charging documents, trial transcripts, investigative reports, sentencing and probation documents, and even any news accounts of the arrest or conviction. Finally, there are limited options in the event of a denial.

What Is the Processing Time for AWA Cases?

Unfortunately, there is no clear cut answer to this question. It is possible that an AWA case be approved in two years (if pressure is applied to USCIS to render a decision). For years after its enactment, the USCIS either denied outright or stalled thousands of visa petitions found to potentially fall within the ambit of the AWA.

What is the BIA’s Position on USCIS Delayed Adjudication of AWA Cases?

The BIA has essentially “washed its hands” of AWA cases. The last effort the BIA made was in 2011 when it remanded an AWA case back to USCIS. In its decision, it specifically asked USCIS to address eight questions that resulted in the denial:

(1)Whether the government has the burden of proving that the petitioner’s conviction is for a “specified offense” against a minor under section 111 of the [Walsh Act]?

(2)Whether the categorical and modified categorical approaches should be used in making the foregoing determination?

(3)If the petitioner was found to have been convicted of a “specified offense” against a minor, is there a rebuttable presumption that the petitioner will pose a risk to the principal beneficiary or a derivative beneficiary?

(4)If the petitioner is found to have been convicted of a “specified offense” against a minor, whether and under what authority, the government applies a “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard in determining—as a matter of discretion—if the petitioner is a risk to the safety or well-being of the principal beneficiary or a derivative beneficiary?

(5)Whether the Director must explain the rationale for his/her conclusion that the petitioner poses a risk to the principal beneficiary or a derivative beneficiary?

(6)As here, where the principal beneficiary is not a minor beneficiary and where there are no minor derivative beneficiaries, does the [Walsh Act] require the petitioner to prove only that he or she poses no risk to the adult principal beneficiary and any adult derivative beneficiaries?

Finally, in the event that the Director denies this visa petition again under the [Walsh Act] and the petitioner files an appeal to this Board, the parties are advised to include a jurisdictional statement. Specifically,

(7)Whether this Board has jurisdiction to review the question of whether the Secretary applied the correct standard in determining whether a petitioner has shown he or she is not a risk to the principal beneficiary or a derivative beneficiary?

(8)What is the nature and scope of the Board’s jurisdiction over other aspects of the appeal?

Rather than address the questions raised in the BIA’s remand, on August 21, 2012, USCIS issued a second NOID on petitioner’s case, and asked that petitioner to provide the exact same information it had originally requested in June of 2010. Counsel for petitioner responded that the information had already been submitted two years earlier.

On January 4, 2013, USCIS filed a motion with the BIA requesting that it reconsider its October, 2011 remand of Petitioner’s I-130 Petition and requesting leave to file a supplemental brief addressing the eight questions the Board presented in its October 2011 remand.

To date, the BIA has not taken any further action on this matter. It has not granted USCIS leave to file its supplemental brief; nor has it agreed to reconsider its October, 2011 remand. Similarly, USCIS has not taken any further action on Petitioner’s I-130 petition, presumably waiting for some action by the BIA in response to its January 2013 submission. Since the Board’s October, 2011 remand, USCIS has not (to our knowledge) officially denied Petitioner’s I130 petition.

On June 29, 2012, petitioner filed suit in the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey, seeking, inter alia, a judgment declaring the Walsh Act inapplicable to the I-130 Petition and ordering USCIS to approve the I-130 Petition. The case was dismissed because as of March 7, 2014, the BIA had not yet responded to or acted upon DHS’s January, 2013 submission (requesting that it reconsider its October 2011 remand). In addition, and perhaps because the remand remains pending, USCIS had not taken any action to officially deny Petitioner’s I-130 Petition since the remand. Since there was no final decision by USCIS for the Court to review, the District Court denied the appeal.

How Do I Know If My Case Falls Under the AWA?

The AWA applies to any USC or LPR who has been convicted of a specified offense against a minor which is broadly defined as an offense against a person under the age of 18 that involves:

- Kidnapping;

- False imprisonment;

- Solicitation to engage in sexual conduct;

- Use in a sexual performance;

- Solicitation to practice prostitution;

- Video voyeurism, possession;

- Production or distribution of child pornography;

- Criminal sexual conduct involving a minor or the use of the Internet to facilitate or attempt such conduct; or

- Any other conduct “that by its nature is a sex offense against a minor

How Can I Win My AWA Case?

You must submit a waiver that proves, beyond any reasonable doubt, to the Department of Homeland Security that he or she poses “no risk” to the beneficiary spouse or fiancé. The “no risk” determination is entirely within the discretion of USCIS. Proving “no risk” can be extremely difficult.

Since the decision relies in the sole discretionary authority of USCIS, the case may still be denied even when the petitioner submits certified records demonstrating successful completion of counseling or rehabilitation programs; certified evaluations by psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, or clinical social workers attesting to the degree of rehabilitation or behavior modification; and other evidence of good character and exemplary service in the community. So it is critical to retain counsel for this matter- please do not take this type of case into your own hands.

What Can an Attorney Do Differently?

There are many different legal strategies an attorney can implement For example, with all of our AWA cases (and criminal cases), the first thing we always do is argue that our client is eligible – in this case, the petitioner’s case is not an AWA case. We do this by arguing that the conviction is not a “sex offense” as mentioned in the last bullet point above.

There are two exceptions to the definition of “sex offense”:

(1)“sex offense” applies to foreign convictions unless they were not obtained “with sufficient safeguards for fundamental fairness and due process for the accused”; or

(2)“sex offense” excludes “offenses involving consensual sexual conduct” between adults unless the adult victim was under the offender’s custodial authority at the time of the offense, or if the victim was at least 13 years old and the offender was not more than 4 years older than the victim”). It all comes down to a few questions:

a.Was the victim an adult? If yes, was the sexual conduct consensual? If no, then it is a “sex offense.”

b.To find out if it was consensual, was the victim under the custodial authority of the offender at the time? If yes, then it was not consensual and it is a “sex offense.”

c.Was the specified age differential present? If yes, then it is not a “sex offense.”

If it is evidence that we are dealing with an AWA case, we file a waiver case to prove that the petitioner does not pose a threat to the beneficiary. Our waiver cases are very thorough, usually between 100 and 200 pages.

My AWA Case Has Been Denied. What Can I Do?

Since 2011, the USCIS has denied the vast majority of applications to waive the AWA bar. There are a few options. First, you can file a motion to reopen and/or reconsider the denial. New evidence can be submitted (if it only recently became available) and errors in the interpretation of law can be flushed out.

Second, you can try and appeal the denial to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and the USCIS District Director. However, in 2014, the BIA held issued a decision that it lacked jurisdiction to review a “no risk” determination made by USCIS. If your case was recently denied by the BIA, you can file an action in Federal Court. Unlike with a naturalization case, you cannot file a Federal Court Action to force USCIS to render a decision, although doing so may put pressure on USCIS.

Third, you can re-file the petition. This approach is best if the petitioner filed the first petition without the assistance of counsel, especially if the record did not contain evidence proving “beyond a reasonable doubt” that the petitioner poses “no threat” to the beneficiary.

The Board of Immigration Appeals has held that: (1) the Adam Walsh Act bar applies regardless of how long ago the conviction occurred; (2) the petitioner bears the burden of proving that a prior conviction is not for a “specified offense against a minor;” (3) USCIS can look at virtually any document related to the arrest and conviction to determine if the bar applies; and, (4) USCIS can demand proof of “no risk” beyond any reasonable doubt, and the BIA will not review USCIS’s determination.

What is the Current Case Law on AWA?

On May 20, 2014, The BIA issued three decisions: Matter of Aceijas-Quiroz, Matter of Introcaso, Matter of Jackson and Erandio. The impact of these three decisions are devastating for those families caught up in the immigration related provisions of the AWA. It now becomes far more likely that their visa petitions will be denied, without any meaningful opportunity to obtain administrative review of such denials. For this reason, it is imperative for petitioners with AWA cases to retain counsel.

In Aceijas-Quiroz, the BIA held that it lacked the authority to review any challenges brought against the legal standard used by USCIS—“beyond a reasonable doubt”—when conducting a “no risk” analysis. Despite this holding, the Board expressed some skepticism about the propriety of that standard, but left the issue to be resolved in another setting, such as a U.S. district court. For the time being, the Board’s decision means that the only AWA-related issue that the Board will review on appeal is whether an individual was convicted of a “specified offense.”

In Introcaso, the BIA explained that a visa petitioner bore the burden of proving whether or not an offense was a “specified offense against a minor.” It held that DHS examiners were not bound by the categorical approach in determining whether any particular offense of which the United States citizen was convicted was for a “specified offense against a minor”. The BIA says that the DHS could look into facts and conduct, whether proven or not during the citizen’s criminal proceeding, to determine if it was a disqualifying offense—even where the elements of the criminal statute at issue would not have supported a finding of ineligibility. Convicted conduct is not the point, per the BIA.

In Jackson and Erandio, the BIA held that the AWA applied to all convictions made by any United States citizen at any time – even those that occurred, as they did in Jackson and Erandio, twenty-five years before the AWA’s enactment. Take, for example, a U.S. citizen who pled guilty to a disqualifying crime in 2000, six years before the AWA took effect. That person could not have known at the time of the criminal proceedings that his guilty plea would later prevent him from petitioning for his foreign-born spouse or stepchildren to come to the U.S. Nevertheless, the BIA held that the AWA was allowed to reach backwards in time, to penalize actions that took place before the law was passed.

How We Can Help?

- We refer clients to one of two specialists who conduct psychological testing and psychosexual testing (as required by USCIS), after which they provide a detailed report that supports our argument that the petitioner “poses no threat to the beneficiary”.

- We refer clients to a forensic psychologist who provides a psychosocial evaluation in support our argument that the petitioner “poses no threat to the beneficiary”.

- We help the petitioner and beneficiary prepare compelling and persuasive Affidavits to bolster the initial filing.

- We prepare and submit a thorough legal memorandum that links the testing evaluations, Affidavits, and supporting documents to present a cohesive package evidencing that the petitioner poses no threat to the beneficiary.

- We have the internal email and contact number for the official who deals with AWA cases held in abeyance. We contact the USCIS office where the case is pending and members of Congress to push for adjudications of cases pending for years.